The History of Genocides

The History of Genocides

The term ‘Genocide’ was coined by Polish writer and attorney, Raphael Lemkin, in 1941 by combining the Greek word ‘genos’ (race) with the Latin word ‘cide’ (killing). Genocide as defined by the United Nations in 1948 means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, including: (a) killing members of the group (b) causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group (c) deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part (d) imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group (e) forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Adopted by the U.N. General Assembly on December 9, 1948.

- Article I.

The Contracting Parties confirm that genocide, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law which they undertake to prevent and punish. - Article II.

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: a) Killing members of the group; b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group. - Article III.

The following acts shall be punished: a) Genocide; b) Conspiracy to commit genocide; c) Direct and public incitement to commit genocide; d) Attempt to commit genocide; e) Complicity in genocide. - Article IV.

Persons committing genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in Article III shall be punished, whether they are constitutionally responsible rulers, public officials or private individuals. - Article V.

The Contracting Parties undertake to enact, in accordance with their respective Constitutions, the necessary legislation to give affect to the provision of the present Convention and, in particular, to provide effective penalties for persons guilty of genocide or of any of the other acts enumerated in Article III. - Article VI.

Persons charged with genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in Article III shall be tried by a competent tribunal of the State in the territory of which the act was committed, or by such international penal tribunal as may have jurisdiction with respect to those Contracting Parties which shall have accepted its jurisdiction. - Article VII.

Genocide and the other acts enumerated in Article III shall not be considered as political crimes for the purpose of extradition. The Contracting Parties pledge themselves in such cases to grant extradition in accordance with their laws and treaties in force. - Article VIII.

Any Contracting Party may call upon the competent organs of the United Nations to take such action under the Charter of the United Nations as they consider appropriate for the prevention and suppression of acts of genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in Article III. - Article IX.

Disputes between the Contracting Parties relating to the interpretation, application or fulfillment of the present Convention, including those relating to the responsibility of a State for genocide or for any of the other acts enumerated in Article III, shall be submitted to the International Court of Justice at the request of any of the parties to the dispute.

Genocide in the 20th Century

Bosnia and Herzegovina 1992 – 1995 200,000 Deaths

In the Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina, conflict between the three main ethnic groups, the Serbs, Croats, and Muslims, resulted in genocide committed by the Serbs against the Muslims in Bosnia.

Bosnia is one of several small countries that emerged from the break-up of Yugoslavia, a multicultural country created after World War I by the victorious Western Allies. Yugoslavia was composed of ethnic and religious groups that had been historical rivals, even bitter enemies, including the Serbs (Orthodox Christians), Croats (Catholics) and ethnic Albanians (Muslims).

During World War II, Yugoslavia was invaded by Nazi Germany and was partitioned. A fierce resistance movement sprang up led by Josip Tito. Following Germany’s defeat, Tito reunified Yugoslavia under the slogan “Brotherhood and Unity,” merging together Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Montenegro, Macedonia, along with two self-governing provinces, Kosovo and Vojvodina.

Tito, a Communist, was a strong leader who maintained ties with the Soviet Union and the United States during the Cold War, playing one superpower against the other while obtaining financial assistance and other aid from both. After his death in 1980 and without his strong leadership, Yugoslavia quickly plunged into political and economic chaos.

A new leader arose by the late 1980s, a Serbian named Slobodan Milosevic, a former Communist who had turned to nationalism and religious hatred to gain power. He began by inflaming long-standing tensions between Serbs and Muslims in the independent provence of Kosovo. Orthodox Christian Serbs in Kosovo were in the minority and claimed they were being mistreated by the Albanian Muslim majority. Serbian-backed political unrest in Kosovo eventually led to its loss of independence and domination by Milosevic.

In June 1991, Slovenia and Croatia both declared their independence from Yugoslavia soon resulting in civil war. The national army of Yugoslavia, now made up of Serbs controlled by Milosevic, stormed into Slovenia but failed to subdue the separatists there and withdrew after only ten days of fighting.

Milosevic quickly lost interest in Slovenia, a country with almost no Serbs. Instead, he turned his attention to Croatia, a Catholic country where Orthodox Serbs made up 12 percent of the population.

During World War II, Croatia had been a pro-Nazi state led by Ante Pavelic and his fascist Ustasha Party. Serbs living in Croatia as well as Jews had been the targets of widespread Ustasha massacres. In the concentration camp at Jasenovac, they had been slaughtered by the tens of thousands.

In 1991, the new Croat government, led by Franjo Tudjman, seemed to be reviving fascism, even using the old Ustasha flag, and also enacted discriminatory laws targeting Orthodox Serbs.

Aided by Serbian guerrillas in Croatia, Milosevic’s forces invaded in July 1991 to ‘protect’ the Serbian minority. In the city of Vukovar, they bombarded the outgunned Croats for 86 consecutive days and reduced it to rubble. After Vukovar fell, the Serbs began the first mass executions of the conflict, killing hundreds of Croat men and burying them in mass graves.

The response of the international community was limited. The U.S. under President George Bush chose not to get involved militarily, but instead recognized the independence of both Slovenia and Croatia. An arms embargo was imposed for all of the former Yugoslavia by the United Nations. However, the Serbs under Milosevic were already the best armed force and thus maintained a big military advantage.

By the end of 1991, a U.S.-sponsored cease-fire agreement was brokered between the Serbs and Croats fighting in Croatia.

In April 1992, the U.S. and European Community chose to recognize the independence of Bosnia, a mostly Muslim country where the Serb minority made up 32 percent of the population. Milosevic responded to Bosnia’s declaration of independence by attacking Sarajevo, its capital city, best known for hosting the 1984 Winter Olympics. Sarajevo soon became known as the city where Serb snipers continually shot down helpless civilians in the streets, including eventually over 3,500 children.

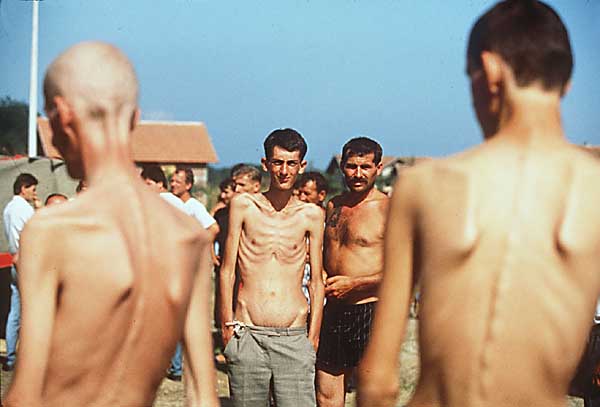

Bosnian Muslims were hopelessly outgunned. As the Serbs gained ground, they began to systematically roundup local Muslims in scenes eerily similar to those that had occurred under the Nazis during World War II, including mass shootings, forced repopulation of entire towns, and confinement in make-shift concentration camps for men and boys. The Serbs also terrorized Muslim families into fleeing their villages by using rape as a weapon against women and girls.

The actions of the Serbs were labeled as ‘ethnic cleansing,’ a name which quickly took hold among the international media.

Despite media reports of the secret camps, the mass killings, as well as the destruction of Muslim mosques and historic architecture in Bosnia, the world community remained mostly indifferent. The U.N. responded by imposing economic sanctions on Serbia and also deployed its troops to protect the distribution of food and medicine to dispossessed Muslims. But the U.N. strictly prohibited its troops from interfering militarily against the Serbs. Thus they remained steadfastly neutral no matter how bad the situation became.

Throughout 1993, confident that the U.N., United States and the European Community would not take militarily action, Serbs in Bosnia freely committed genocide against Muslims. Bosnian Serbs operated under the local leadership of Radovan Karadzic, president of the illegitimate Bosnian Serb Republic. Karadzic had once told a group of journalists, “Serbs and Muslims are like cats and dogs. They cannot live together in peace. It is impossible.”

When Karadzic was confronted by reporters about ongoing atrocities, he bluntly denied involvement of his soldiers or special police units.

On February 6, 1994, the world’s attention turned completely to Bosnia as a marketplace in Sarajevo was struck by a Serb mortar shell killing 68 persons and wounding nearly 200. Sights and sounds of the bloody carnage were broadcast globally by the international news media and soon resulted in calls for military intervention against the Serbs.

The U.S. under its new President, Bill Clinton, who had promised during his election campaign in 1992 to stop the ethnic cleansing in Bosnia, now issued an ultimatum through the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) demanding that the Serbs withdraw their artillery from Sarajevo. The Serbs quickly complied and a NATO-imposed cease-fire in Sarajevo was declared.

The U.S. then launched diplomatic efforts aimed at unifying Bosnian Muslims and the Croats against the Serbs. However, this new Muslim-Croat alliance failed to stop the Serbs from attacking Muslim towns in Bosnia which had been declared Safe Havens by the U.N. A total of six Muslim towns had been established as Safe Havens in May 1993 under the supervision of U.N. peacekeepers.

Bosnian Serbs not only attacked the Safe Havens but also attacked the U.N. peacekeepers as well. NATO forces responded by launching limited air strikes against Serb ground positions. The Serbs retaliated by taking hundreds of U.N. peacekeepers as hostages and turning them into human shields, chained to military targets such as ammo supply dumps.

At this point, some of the worst genocidal activities of the four-year-old conflict occurred. In Srebrenica, a Safe Haven, U.N. peacekeepers stood by helplessly as the Serbs under the command of General Ratko Mladic systematically selected and then slaughtered nearly 8,000 men and boys between the ages of twelve and sixty - the worst mass murder in Europe since World War II. In addition, the Serbs continued to engage in mass rapes of Muslim females.

On August 30, 1995, effective military intervention finally began as the U.S. led a massive NATO bombing campaign in response to the killings at Srebrenica, targeting Serbian artillery positions throughout Bosnia. The bombardment continued into October. Serb forces also lost ground to Bosnian Muslims who had received arms shipments from the Islamic world. As a result, half of Bosnia was eventually retaken by Muslim-Croat troops.

Faced with the heavy NATO bombardment and a string of ground losses to the Muslim-Croat alliance, Serb leader Milosevic was now ready to talk peace. On November 1, 1995, leaders of the warring factions including Milosevic and Tudjman traveled to the U.S. for peace talks at Wright-Patterson Air Force base in Ohio.

After three weeks of negotiations, a peace accord was declared. Terms of the agreement included partitioning Bosnia into two main portions known as the Bosnian Serb Republic and the Muslim-Croat Federation. The agreement also called for democratic elections and stipulated that war criminals would be handed over for prosecution. 60,000 NATO soldiers were deployed to preserve the cease-fire.

By now, over 200,000 Muslim civilians had been systematically murdered. More than 20,000 were missing and feared dead, while 2,000,000 had become refugees. It was, according to U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Richard Holbrooke, “the greatest failure of the West since the 1930s.”

Rwanda 1994 800,000 Deaths

Beginning on April 6, 1994, and for the next hundred days, up to 800,000 Tutsis were killed by Hutu militia using clubs and machetes, with as many as 10,000 killed each day.

Rwanda is one of the smallest countries in Central Africa, with just 7 million people, and is comprised of two main ethnic groups, the Hutu and the Tutsi. Although the Hutus account for 90 percent of the population, in the past, the Tutsi minority was considered the aristocracy of Rwanda and dominated Hutu peasants for decades, especially while Rwanda was under Belgian colonial rule.

Following independence from Belgium in 1962, the Hutu majority seized power and reversed the roles, oppressing the Tutsis through systematic discrimination and acts of violence. As a result, over 200,000 Tutsis fled to neighboring countries and formed a rebel guerrilla army, the Rwandan Patriotic Front.

In 1990, this rebel army invaded Rwanda and forced Hutu President Juvenal Habyalimana into signing an accord which mandated that the Hutus and Tutsis would share power.

Ethnic tensions in Rwanda were significantly heightened in October 1993 upon the assassination of Melchior Ndadaye, the first popularly elected Hutu president of neighboring Burundi.

A United Nations peacekeeping force of 2,500 multinational soldiers was then dispatched to Rwanda to preserve the fragile cease-fire between the Hutu government and the Tutsi rebels. Peace was threatened by Hutu extremists who were violently opposed to sharing any power with the Tutsis. Among these extremists were those who desired nothing less than the actual extermination of the Tutsis. It was later revealed they had even drawn up lists of prominent Tutsis and moderate Hutu politicians to kill, should the opportunity arise.

In April 1994, amid ever-increasing prospects of violence, Rwandan President Habyalimana and Burundi’s new President, Cyprien Ntaryamira, held several peace meetings with Tutsi rebels. On April 6, while returning from a meeting in Tanzania, a small jet carrying the two presidents was shot down by ground-fired missiles as it approached Rwanda’s airport at Kigali. Immediately after their deaths, Rwanda plunged into political violence as Hutu extremists began targeting prominent opposition figures who were on their death-lists, including moderate Hutu politicians and Tutsi leaders.

The killings then spread throughout the countryside as Hutu militia, armed with machetes, clubs, guns and grenades, began indiscriminately killing Tutsi civilians. All individuals in Rwanda carried identification cards specifying their ethnic background, a practice left over from colonial days. These ‘tribal cards’ now meant the difference between life and death.

Amid the onslaught, the small U.N. peacekeeping force was overwhelmed as terrified Tutsi families and moderate politicians sought protection.

Among the peacekeepers were ten soldiers from Belgium who were captured by the Hutus, tortured and murdered. As a result, the United States, France, Belgium, and Italy all began evacuating their own personnel from Rwanda.

However, no effort was made to evacuate Tutsi civilians or Hutu moderates. Instead, they were left behind entirely at the mercy of the avenging Hutu.

Back at U.N headquarters in New York, the killings were initially categorized as a breakdown in the cease-fire between the Tutsi and Hutu. Throughout the massacre, both the U.N. and the U.S. carefully refrained from labeling the killings as genocide, which would have necessitated some kind of emergency intervention.

On April 21, the Red Cross estimated that hundreds of thousands of Tutsi had already been massacred since April 6 - an extraordinary rate of killing.

The U.N. Security Council responded to the worsening crisis by voting unanimously to abandon Rwanda. The remainder of U.N. peacekeeping troops were pulled out, leaving behind a only tiny force of about 200 soldiers for the entire country.

The Hutu, now without opposition from the world community, engaged in genocidal mania, clubbing and hacking to death defenseless Tutsi families with machetes everywhere they were found. The Rwandan state radio, controlled by Hutu extremists, further encouraged the killings by broadcasting non-stop hate propaganda and even pinpointed the locations of Tutsis in hiding. The killers were aided by members of the Hutu professional class including journalists, doctors and educators, along with unemployed Hutu youths and peasants who killed Tutsis just to steal their property.

Many Tutsis took refuge in churches and mission compounds. These places became the scenes of some of the worst massacres. In one case, at Musha, 1,200 Tutsis who had sought refuge were killed beginning at 8 a.m. lasting until the evening. Hospitals also became prime targets as wounded survivors were sought out then killed.

In some local villages, militiamen forced Hutus to kill their Tutsi neighbors or face a death sentence for themselves and their entire families. They also forced Tutsis to kill members of their own families.

By mid May, an estimated 500,000 Tutsis had been slaughtered. Bodies were now commonly seen floating down the Kigara River into Lake Victoria.

Confronted with international TV news reports depicting genocide, the U.N. Security Council voted to send up to 5,000 soldiers to Rwanda. However, the Security Council failed to establish any timetable and thus never sent the troops in time to stop the massacre.

The killings only ended after armed Tutsi rebels, invading from neighboring countries, managed to defeat the Hutus and halt the genocide in July 1994. By then, over one-tenth of the population, an estimated 800,000 persons, had been killed.

Pol Pot in Cambodia 1975 – 1979 2,000,000Deaths

An attempt by Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot to form a Communist peasant farming society resulted in the deaths of 25 percent of the country’s population from starvation, overwork and executions.

Pol Pot was born in 1925 (as Saloth Sar) into a farming family in central Cambodia, which was then part of French Indochina. In 1949, at age 20, he traveled to Paris on a scholarship to study radio electronics but became absorbed in Marxism and neglected his studies. He lost his scholarship and returned to Cambodia in 1953 and joined the underground Communist movement. The following year, Cambodia achieved full independence from France and was then ruled by a royal monarchy.

By 1962, Pol Pot had become leader of the Cambodian Communist Party and was forced to flee into the jungle to escape the wrath of Prince Norodom Sihanouk, leader of Cambodia. In the jungle, Pol Pot formed an armed resistance movement that became known as the Khmer Rouge (Red Cambodians) and waged a guerrilla war against Sihanouk’s government.

In 1970, Prince Sihanouk was ousted, not by Pol Pot, but due to a U.S.-backed right-wing military coup. An embittered Sihanouk retaliated by joining with Pol Pot, his former enemy, in opposing Cambodia’s new military government. That same year, the U.S. invaded Cambodia to expel the North Vietnamese from their border encampments, but instead drove them deeper into Cambodia where they allied themselves with the Khmer Rouge.

From 1969 until 1973, the U.S. intermittently bombed North Vietnamese sanctuaries in eastern Cambodia, killing up to 150,000 Cambodian peasants. As a result, peasants fled the countryside by the hundreds of thousands and settled in Cambodia’s capital city, Phnom Penh.

All of these events resulted in economic and military destabilization in Cambodia and a surge of popular support for Pol Pot.

By 1975, the U.S. had withdrawn its troops from Vietnam. Cambodia’s government, plagued by corruption and incompetence, also lost its American military support. Taking advantage of the opportunity, Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge army, consisting of teenage peasant guerrillas, marched into Phnom Penh and on April 17 effectively seized control of Cambodia.

Once in power, Pol Pot began a radical experiment to create an agrarian utopia inspired in part by Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution which he had witnessed first-hand during a visit to Communist China.

Mao’s “Great Leap Forward” economic program included forced evacuations of Chinese cities and the purging of “class enemies.” Pol Pot would now attempt his own “Super Great Leap Forward” in Cambodia, which he renamed the Democratic Republic of Kampuchea.

He began by declaring, “This is Year Zero,” and that society was about to be “purified.” Capitalism, Western culture, city life, religion, and all foreign influences were to be extinguished in favor of an extreme form of peasant Communism.

All foreigners were thus expelled, embassies closed, and any foreign economic or medical assistance was refused. The use of foreign languages was banned. Newspapers and television stations were shut down, radios and bicycles confiscated, and mail and telephone usage curtailed. Money was forbidden. All businesses were shuttered, religion banned, education halted, health care eliminated, and parental authority revoked. Thus Cambodia was sealed off from the outside world.

All of Cambodia’s cities were then forcibly evacuated. At Phnom Penh, two million inhabitants were evacuated on foot into the countryside at gunpoint. As many as 20,000 died along the way.

Millions of Cambodians accustomed to city life were now forced into slave labor in Pol Pot’s “killing fields” where they soon began dying from overwork, malnutrition and disease, on a diet of one tin of rice (180 grams) per person every two days.

Workdays in the fields began around 4 a.m. and lasted until 10 p.m., with only two rest periods allowed during the 18 hour day, all under the armed supervision of young Khmer Rouge soldiers eager to kill anyone for the slightest infraction. Starving people were forbidden to eat the fruits and rice they were harvesting. After the rice crop was harvested, Khmer Rouge trucks would arrive and confiscate the entire crop.

Ten to fifteen families lived together with a chairman at the head of each group. All work decisions were made by the armed supervisors with no participation from the workers who were told, “Whether you live or die is not of great significance.” Every tenth day was a day of rest. There were also three days off during the Khmer New Year festival.

Throughout Cambodia, deadly purges were conducted to eliminate remnants of the “old society” - the educated, the wealthy, Buddhist monks, police, doctors, lawyers, teachers, and former government officials. Ex-soldiers were killed along with their wives and children. Anyone suspected of disloyalty to Pol Pot, including eventually many Khmer Rouge leaders, was shot or bludgeoned with an ax. “What is rotten must be removed,” a Khmer Rouge slogan proclaimed.

In the villages, unsupervised gatherings of more than two persons were forbidden. Young people were taken from their parents and placed in communals. They were later married in collective ceremonies involving hundreds of often-unwilling couples.

Up to 20,000 persons were tortured into giving false confessions at Tuol Sleng, a school in Phnom Penh which had been converted into a jail. Elsewhere, suspects were often shot on the spot before any questioning.

Ethnic groups were attacked including the three largest minorities; the Vietnamese, Chinese, and Cham Muslims, along with twenty other smaller groups. Fifty percent of the estimated 425,000 Chinese living in Cambodia in 1975 perished. Khmer Rouge also forced Muslims to eat pork and shot those who refused.

On December 25, 1978, Vietnam launched a full-scale invasion of Cambodia seeking to end Khmer Rouge border attacks. On January 7, 1979, Phnom Penh fell and Pol Pot was deposed. The Vietnamese then installed a puppet government consisting of Khmer Rouge defectors.

Pol Pot retreated into Thailand with the remnants of his Khmer Rouge army and began a guerrilla war against a succession of Cambodian governments lasting over the next 17 years. After a series of internal power struggles in the 1990s, he finally lost control of the Khmer Rouge. In April 1998, 73-year-old Pol Pot died of an apparent heart attack following his arrest, before he could be brought to trial by an international tribunal for the events of 1975-79.

The Nazi Holocaust 1939 – 1945 6,000,000 Deaths

It began with a simple boycott of Jewish shops and ended in the gas chambers at Auschwitz as Adolf Hitler and his Nazi followers attempted to exterminate the entire Jewish population of Europe.

In January 1933, after a bitter ten-year political struggle, Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany. During his rise to power, Hitler had repeatedly blamed the Jews for Germany’s defeat in World War I and subsequent economic hardships. Hitler also put forward racial theories asserting that Germans with fair skin, blond hair and blue eyes were the supreme form of human, or master race. The Jews, according to Hitler, were the racial opposite, and were actively engaged in an international conspiracy to keep this master race from assuming its rightful position as rulers of the world.

Jews at this time composed only about one percent of Germany’s population of 55 million persons. German Jews were mostly cosmopolitan in nature and proudly considered themselves to be Germans by nationality and Jews only by religion. They had lived in Germany for centuries, fought bravely for the Fatherland in its wars and prospered in numerous professions.

But they were gradually shut out of German society by the Nazis through a never-ending series of laws and decrees, culminating in the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 which deprived them of their German citizenship and forbade intermarriage with non-Jews. They were removed from schools, banned from the professions, excluded from military service, and were even forbidden to share a park bench with a non-Jew.

At the same time, a carefully orchestrated smear campaign under the direction of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels portrayed Jews as enemies of the German people. Daily anti-Semitic slurs appeared in Nazi newspapers, on posters, the movies, radio, in speeches by Hitler and top Nazis, and in the classroom. As a result, State-sanctioned anti-Semitism became the norm throughout Germany. The Jews lost everything, including their homes and businesses, with no protest or public outcry from non-Jewish Germans. The devastating Nazi propaganda film The Eternal Jew went so far as to compared Jews to plague carrying rats, a foreshadow of things to come.

In March 1938, Hitler expanded the borders of the Nazi Reich by forcibly annexing Austria. A brutal crackdown immediately began on Austria’s Jews. They also lost everything and were even forced to perform public acts of humiliation such as scrubbing sidewalks clean amid jeering pro-Nazi crowds.

Back in Germany, years of pent-up hatred toward the Jews was finally let loose on the night that marks the actual beginning of the Holocaust. The Night of Broken Glass (Kristallnacht) occurred on November 9/10 after 17-year-old Herschel Grynszpan shot and killed Ernst vom Rath, a German embassy official in Paris, in retaliation for the harsh treatment his Jewish parents had received from Nazis.

Spurred on by Joseph Goebbels, Nazis used the death of vom Rath as an excuse to conduct the first State-run pogrom against Jews. Ninety Jews were killed, 500 synagogues were burned and most Jewish shops had their windows smashed. The first mass arrest of Jews also occurred as over 25,000 men were hauled off to concentration camps. As a kind of cynical joke, the Nazis then fined the Jews 1 Billion Reichsmarks for the destruction which the Nazis themselves had caused during Kristallnacht.

Many German and Austrian Jews now attempted to flee Hitler’s Reich. However, most Western countries maintained strict immigration quotas and showed little interest in receiving large numbers of Jewish refugees. This was exemplified by the plight of the St. Louis, a ship crowded with 930 Jews that was turned away by Cuba, the United States and other countries and returned back to Europe, soon to be under Hitler’s control.

On the eve of World War II, the Führer (supreme leader) publicly threatened the Jews of Europe during a speech in Berlin: “In the course of my life I have very often been a prophet, and have usually been ridiculed for it. During the time of my struggle for power it was in the first instance only the Jewish race that received my prophecies with laughter when I said that I would one day take over the leadership of the State, and with it that of the whole nation, and that I would then among other things settle the Jewish problem. Their laughter was uproarious, but I think that for some time now they have been laughing on the other side of their face. Today I will once more be a prophet: if the international Jewish financiers in and outside Europe should succeed in plunging the nations once more into a world war, then the result will not be the Bolshevizing of the earth, and thus the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe!”

Hitler intended to blame the Jews for the new world war he was soon to provoke. That war began in September 1939 as German troops stormed into Poland, a country that was home to over three million Jews. After Poland’s quick defeat, Polish Jews were rounded up and forced into newly established ghettos at Lodz, Krakow, and Warsaw, to await future plans. Inside these overcrowded walled-in ghettos, tens of thousands died a slow death from hunger and disease amid squalid living conditions. The ghettos soon came under the jurisdiction of Heinrich Himmler, leader of the Nazi SS, Hitler’s most trusted and loyal organization, composed of fanatical young men considered racially pure according to Nazi standards.

In the spring of 1940, Himmler ordered the building of a concentration camp near the Polish city of Oswiecim, renamed Auschwitz by the Germans, to hold Polish prisoners and to provide slave labor for new German-run factories to be built nearby.

Meanwhile, Hitler continued his conquest of Europe, invading Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg and France, placing ever-increasing numbers of Jews under Nazi control. The Nazis then began carefully tallying up the actual figures and also required Jews to register all of their assets. But the overall question remained as to what to do with the millions of Jews now under Nazi control - referred to by the Nazis themselves as the Judenfrage (Jewish question).

The following year, 1941, would be the turning point. In June, Hitler took a tremendous military gamble by invading the Soviet Union. Before the invasion he had summoned his top generals and told them the attack on Russia would be a ruthless “war of annihilation” targeting Communists and Jews and that normal rules of military conflict were to be utterly ignored.

Inside the Soviet Union were an estimated three million Jews, many of whom still lived in tiny isolated villages known as Shtetls. Following behind the invading German armies, four SS special action units known as Einsatzgruppen systematically rounded-up and shot all of the inhabitants of these Shtetls. Einsatz execution squads were aided by German police units, local ethnic Germans, and local anti-Semitic volunteers. Leaders of the Einsatzgruppen also engaged in an informal competition as to which group had the highest tally of murdered Jews.

During the summer of 1941, SS leader Heinrich Himmler summoned Auschwitz Commandant Rudolf Höss to Berlin and told him: “The Führer has ordered the Final Solution of the Jewish question. We, the SS, have to carry out this order…I have therefore chosen Auschwitz for this purpose.”

At Auschwitz, a large new camp was already under construction to be known as Auschwitz II (Birkenau). This would become the future site of four large gas chambers to be used for mass extermination. The idea of using gas chambers originated during the Euthanasia Program, the so-called “mercy killing” of sick and disabled persons in Germany and Austria by Nazi doctors.

By now, experimental mobile gas vans were being used by the Einsatzgruppen to kill Jews in Russia. Special trucks had been converted by the SS into portable gas chambers. Jews were locked up in the air-tight rear container while exhaust fumes from the truck’s engine were fed in to suffocate them. However, this method was found to be somewhat impractical since the average capacity was less than 50 persons. For the time being, the quickest killing method continued to be mass shootings. And as Hitler’s troops advanced deep into the Soviet Union, the pace of Einsatz killings accelerated. Over 33,000 Jews in the Ukraine were shot in the Babi Yar ravine near Kiev during two days in September 1941.

The next year, 1942, marked the beginning of mass murder on a scale unprecedented in all of human history. In January, fifteen top Nazis led by Reinhard Heydrich, second in command of the SS, convened the Wannsee Conference in Berlin to coordinate plans for the Final Solution. The Jews of Europe would now be rounded up and deported into occupied Poland where new extermination centers were being constructed at Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, and Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Code named “Aktion Reinhard” in honor of Heydrich, the Final Solution began in the spring as over two million Jews already in Poland were sent to be gassed as soon as the new camps became operational. Hans Frank, the Nazi Governor of Poland had by now declared: “I ask nothing of the Jews except that they should disappear.”

Every detail of the actual extermination process was meticulously planned. Jews arriving in trains at Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka were falsely informed by the SS that they had come to a transit stop and would be moving on to their true destination after delousing. They were told their clothes were going to be disinfected and that they would all be taken to shower rooms for a good washing. Men were then split up from the women and children. Everyone was taken to undressing barracks and told to remove all of their clothing. Women and girls next had their hair cut off. First the men, and then the women and children, were hustled in the nude along a narrow fenced-in pathway nicknamed by the SS as the Himmelstrasse (road to Heaven). At the end of the path was a bathhouse with tiled shower rooms. As soon as the people were all crammed inside, the main door was slammed shut, creating an air-tight seal. Deadly carbon monoxide fumes were then fed in from a stationary diesel engine located outside the chamber.

At Auschwitz-Birkenau, new arrivals were told to carefully hang their clothing on numbered hooks in the undressing room and were instructed to remember the numbers for later. They were given a piece of soap and taken into the adjacent gas chamber disguised as a large shower room. In place of carbon monoxide, pellets of the commercial pesticide Zyklon-B (prussic acid) were poured into openings located above the chamber upon the cynical SS command - Na, gib ihnen shon zu fressen (All right, give ‘em something to chew on). The gas pellets fell into hollow shafts made of perforated sheet metal and vaporized upon contact with air, giving off lethal cyanide fumes inside the chamber which oozed out at floor level then rose up toward the ceiling. Children died first since they were closer to the floor. Pandemonium usually erupted as the bitter almond-like odor of the gas spread upwards with adults climbing on top of each other forming a tangled heap of dead bodies all the way up to the ceiling.

At each of the death camps, special squads of Jewish slave laborers called Sonderkommandos were utilized to untangle the victims and remove them from the gas chamber. Next they extracted any gold fillings from teeth and searched body orifices for hidden valuables. The corpses were disposed of by various methods including mass burials, cremation in open fire pits or in specially designed crematory ovens such as those used at Auschwitz. All clothing, money, gold, jewelry, watches, eyeglasses and other valuables were sorted out then shipped back to Germany for re-use. Women’s hair was sent to a firm in Bavaria for the manufacture of felt.

One extraordinary aspect of the journey to the death camps was that the Nazis often charged Jews deported from Western Europe train fare as third class passengers under the guise that they were being “resettled in the East.” The SS also made new arrivals in the death camps sign picture postcards showing the fictional location “Waldsee” which were sent to relatives back home with the printed greeting: “We are doing very well here. We have work and we are well treated. We await your arrival.”

In the ghettos of Poland, Jews were simply told they were being “transferred” to work camps. Many went willingly, hoping to escape the brutal ghetto conditions. They were then stuffed into unheated, poorly ventilated boxcars with no water or sanitation. Young children and the elderly often died long before reaching their destination.

Trainloads of human cargo arriving at Auschwitz went through a selection process conducted by SS doctors such as Josef Mengele. Young adults considered fit for slave labor were allowed to live and had an ID number tattooed on their left forearm. Everyone else went to the gas chambers. A few inmates, including twin children, were occasionally set aside for participation in human medical experiments.

The death camp at Majdanek operated on the Auschwitz model and served both as a slave labor camp and extermination center. Chelmno, the sixth death camp in occupied Poland, operated somewhat differently from the others in that large mobile gas vans were continually used.

Although the Nazis attempted to keep all of the death camps secret, rumors and some eyewitness reports gradually filtered out. Harder to conceal were the mass shootings occurring throughout occupied Russia. On June 30 and July 2, 1942, the New York Times reported via the London Daily Telegraph that over 1,000,000 Jews had already been shot.

That summer, Swiss representatives of the World Jewish Congress received information from a German industrialist regarding the Nazi plan to exterminate the Jews. They passed the information on to London and Washington.

In December 1942, British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden stood before the House of Commons and declared the Nazis were “now carrying into effect Hitler’s oft-repeated intention to exterminate the Jewish people of Europe.”

Jews in America responded to the various reports by holding a rally at New York’s Madison Square Garden in March 1943 to pressure the U.S. government into action. As a result, the Bermuda Conference was held from April 19-30, with representatives from the U.S. and Britain meeting to discuss the problem of refugees from Nazi-occupied countries. But the meeting resulted in complete inaction concerning the ongoing exterminations.

Seven months later, November 1943, the U.S. Congress held hearings concerning the U.S. State Department’s total inaction regarding the plight of European Jews. President Franklin Roosevelt responded to the mounting political pressure by creating the War Refugee Board (WRB) in January 1944 to aid neutral countries in the rescue of Jews. The WRB helped save about 200,000 Jews from death camps through the heroic efforts of persons such as Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg working tirelessly in occupied countries.

The WRB also advocated the aerial bombing of Auschwitz, although it never occurred since it was not considered a vital military target. The U.S. and its military Allies maintained that the best way to stop Nazi atrocities was to defeat Germany as quickly as possible.

In April 1944, two Jewish inmates escaped from Auschwitz and made it safely into Czechoslovakia. One of them, Rudolf Vrba, submitted a detailed report to the Papal Nuncio in Slovakia which was then forwarded to the Vatican, received there in mid-June. Thus far, Pope Pius XII had not issued a public condemnation of Nazi maltreatment and subsequent mass murder of Jews, and he chose to continue his silence.

The Nazis attempted to quell increasing reports of the Final Solution by inviting the International Red Cross to visit Theresienstadt, a ghetto in Czechoslovakia containing prominent Jews. A Red Cross delegation toured Theresienstadt in July 1944 observing stores, banks, cafes, and classrooms which had been hastily spruced-up for their benefit. They also witnessed a delightful musical program put on by Jewish children. After the Red Cross departed, most of the ghetto inhabitants, including all of the children, were sent to be gassed and the model village was left to deteriorate.

In several instances, Jews took matters into their own hands and violently resisted the Nazis. The most notable was the 28-day battle waged inside the Warsaw Ghetto. There, a group of 750 Jews armed with smuggled-in weapons battled over 2000 SS soldiers armed with small tanks, artillery and flame throwers. Upon encountering stiff resistance from the Jews, the Nazis decided to burn down the entire ghetto.

An SS report described the scene: “The Jews stayed in the burning buildings until because of the fear of being burned alive they jumped down from the upper stories�With their bones broken, they still tried to crawl across the street into buildings which had not yet been set on fire�Despite the danger of being burned alive the Jews and bandits often preferred to return into the flames rather than risk being caught by us.”

Resistance also occurred inside the death camps. At Treblinka, Jewish inmates staged a revolt in August 1943, after which Himmler ordered the camp dismantled. At Sobibor, a big escape occurred in October 1943, as Jews and Soviet POWs killed 11 SS men and broke out, with 300 making it safely into nearby woods. Of those 300, most were hunted down and only fifty survived. Himmler then closed Sobibor. At Auschwitz-Birkenau, Jewish Sonderkommandos managed to destroy crematory number four in October 1944.

But throughout Nazi-occupied Europe, relatively few non-Jewish persons were willing to risk their own lives to help the Jews. Notable exceptions included Oskar Schindler, a German who saved 1200 Jews by moving them from Plaszow labor camp to his hometown of Brunnlitz. The country of Denmark rescued nearly its entire population of Jews, over 7000, by transporting them to safety by sea. Italy and Bulgaria both refused to cooperate with German demands for deportations. Elsewhere in Europe, people generally stood by passively and watched as Jewish families were marched through the streets toward waiting trains, or in some cases, actively participated in Nazi persecutions.

By 1944, the tide of war had turned against Hitler and his armies were being defeated on all fronts by the Allies. However, the killing of Jews continued uninterrupted. Railroad locomotives and freight cars badly needed by the German Army were instead used by the SS to transport Jews to Auschwitz.

In May, Nazis under the direction of SS Lt. Colonel Adolf Eichmann boldly began a mass deportation of the last major surviving population of European Jews. From May 15 to July 9, over 430,000 Hungarian Jews were deported to Auschwitz. During this time, Auschwitz recorded its highest-ever daily number of persons killed and cremated at just over 9000. Six huge open pits were used to burn the bodies, as the number of dead exceeded the capacity of the crematories.

The unstoppable Allied military advance continued and on July 24, 1944, Soviet troops liberated the first camp, Majdanek in eastern Poland, where over 360,000 had died. As the Soviet Army neared Auschwitz, Himmler ordered the complete destruction of the gas chambers. Throughout Hitler’s crumbling Reich, the SS now began conducting death marches of surviving concentration camp inmates away from outlying areas, including some 66,000 from Auschwitz. Most of the inmates on these marches either dropped dead from exertion or were shot by the SS when they failed to keep up with the column.

The Soviet Army reached Auschwitz on January 27, 1945. By that time, an estimated 1,500,000 Jews, along with 500,000 Polish prisoners, Soviet POWs and Gypsies, had perished there. As the Western Allies pushed into Germany in the spring of 1945, they liberated Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen, and Dachau. Now the full horror of the twelve-year Nazi regime became apparent as British and American soldiers, including Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower, viewed piles of emaciated corpses and listened to vivid accounts given by survivors.

On April 30, 1945, surrounded by the Soviet Army in Berlin, Adolf Hitler committed suicide and his Reich soon collapsed. By now, most of Europe’s Jews had been killed. Four million had been gassed in the death camps while another two million had been shot dead or died in the ghettos. The victorious Allies; Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union, then began the daunting task of sorting through the carnage to determine exactly who was responsible. Seven months later, the Nuremberg War Crime Trials began, with 22 surviving top Nazis charged with crimes against humanity.

During the trial, a now-repentant Hans Frank, the former Nazi Governor of Poland declared: “A thousand years will pass and the guilt of the Germany will not be erased.”

The Rape of Nanking 1937 – 1938 300,000 Deaths

In December of 1937, the Japanese Imperial Army marched into China’s capital city of Nanking and proceeded to murder 300,000 out of 600,000 civilians and soldiers in the city. The six weeks of carnage would become known as the Rape of Nanking and represented the single worst atrocity during the World War II era in either the European or Pacific theaters of war.

The actual military invasion of Nanking was preceded by a tough battle at Shanghai that began in the summer of 1937. Chinese forces there put up surprisingly stiff resistance against the Japanese Army which had expected an easy victory in China. The Japanese had even bragged they would conquer all of China in just three months. The stubborn resistance by the Chinese troops upset that timetable, with the battle dragging on through the summer into late fall. This infuriated the Japanese and whetted their appetite for the revenge that was to follow at Nanking.

After finally defeating the Chinese at Shanghai in November, 50,000 Japanese soldiers then marched on toward Nanking. Unlike the troops at Shanghai, Chinese soldiers at Nanking were poorly led and loosely organized. Although they greatly outnumbered the Japanese and had plenty of ammunition, they withered under the ferocity of the Japanese attack, then engaged in a chaotic retreat. After just four days of fighting, Japanese troops smashed into the city on December 13, 1937, with orders issued to “kill all captives.”

Their first concern was to eliminate any threat from the 90,000 Chinese soldiers who surrendered. To the Japanese, surrender was an unthinkable act of cowardice and the ultimate violation of the rigid code of military honor drilled into them from childhood onward. Thus they looked upon Chinese POWs with utter contempt, viewing them as less than human, unworthy of life.

The elimination of the Chinese POWs began after they were transported by trucks to remote locations on the outskirts of Nanking. As soon as they were assembled, the savagery began, with young Japanese soldiers encouraged by their superiors to inflict maximum pain and suffering upon individual POWs as a way of toughening themselves up for future battles, and also to eradicate any civilized notions of mercy. Filmed footage and still photographs taken by the Japanese themselves document the brutality. Smiling soldiers can be seen conducting bayonet practice on live prisoners, decapitating them and displaying severed heads as souvenirs, and proudly standing among mutilated corpses. Some of the Chinese POWs were simply mowed down by machine-gun fire while others were tied-up, soaked with gasoline and burned alive.

After the destruction of the POWs, the soldiers turned their attention to the women of Nanking and an outright animalistic hunt ensued. Old women over the age of 70 as well as little girls under the age of 8 were dragged off to be sexually abused. More than 20,000 females (with some estimates as high as 80,000) were gang-raped by Japanese soldiers, then stabbed to death with bayonets or shot so they could never bear witness.

Pregnant women were not spared. In several instances, they were raped, then had their bellies slit open and the fetuses torn out. Sometimes, after storming into a house and encountering a whole family, the Japanese forced Chinese men to rape their own daughters, sons to rape their mothers, and brothers their sisters, while the rest of the family was made to watch.

Throughout the city of Nanking, random acts of murder occurred as soldiers frequently fired their rifles into panicked crowds of civilians, killing indiscriminately. Other soldiers killed shopkeepers, looted their stores, then set the buildings on fire after locking people of all ages inside. They took pleasure in the extraordinary suffering that ensued as the people desperately tried to escape the flames by climbing onto rooftops or leaping down onto the street.

The incredible carnage - citywide burnings, stabbings, drownings, strangulations, rapes, thefts, and massive property destruction - continued unabated for about six weeks, from mid-December 1937 through the beginning of February 1938. Young or old, male or female, anyone could be shot on a whim by any Japanese soldier for any reason. Corpses could be seen everywhere throughout the city. The streets of Nanking were said to literally have run red with blood.

Those who were not killed on the spot were taken to the outskirts of the city and forced to dig their own graves, large rectangular pits that would be filled with decapitated corpses resulting from killing contests the Japanese held among themselves. Other times, the Japanese forced the Chinese to bury each other alive in the dirt.

After this period of unprecedented violence, the Japanese eased off somewhat and settled in for the duration of the war. To pacify the population during the long occupation, highly addictive narcotics, including opium and heroin, were distributed by Japanese soldiers to the people of Nanking, regardless of age. An estimated 50,000 persons became addicted to heroin while many others lost themselves in the city’s opium dens.

In addition, the notorious Comfort Women system was introduced which forced young Chinese women to become slave-prostitutes, existing solely for the sexual pleasure of Japanese soldiers.

News reports of the happenings in Nanking appeared in the official Japanese press and also in the West, as page-one reports in newspapers such as the New York Times. Japanese news reports reflected the militaristic mood of the country in which any victory by the Imperial Army resulting in further expansion of the Japanese empire was celebrated. Eyewitness reports by Japanese military correspondents concerning the sufferings of the people of Nanking also appeared. They reflected a mentality in which the brutal dominance of subjugated or so-called inferior peoples was considered just. Incredibly, one paper, the Japan Advertiser, actually published a running count of the heads severed by two officers involved in a decapitation contest, as if it was some kind of a sporting match.

In the United States, reports published in the New York Times, Reader’s Digest and Time Magazine, were greeted with skepticism from the American public. The stories smuggled out of Nanking seemed almost too fantastic to be believed.

Overall, most Americans had only a passing knowledge or little interest in Asia. Political leaders in both America and Britain remained overwhelmingly focused on the situation in Europe where Adolf Hitler was rapidly re-arming Germany while at the same time expanding the borders of the Nazi Reich through devious political maneuvers.

Back in Nanking, however, all was not lost. An extraordinary group of about 20 Americans and Europeans remaining in the city, composed of missionaries, doctors and businessmen, took it upon themselves to establish an International Safety Zone. Using Red Cross flags, they brazenly declared a 2.5 square-mile area in the middle of the city off limits to the Japanese. On numerous occasions, they also risked their lives by personally intervening to prevent the execution of Chinese men or the rape of women and young girls.

These Westerners became the unsung heroes of Nanking, working day and night to the point of exhaustion to aid the Chinese. They also wrote down their impressions of the daily scenes they witnessed, with one describing Nanking as “hell on earth.” Another wrote of the Japanese soldiers: “I did not imagine that such cruel people existed in the modern world.” About 300,000 Chinese civilians took refuge inside their Safety Zone. Almost all of the people who did not make it into the Zone during the Rape of Nanking ultimately perished.

Stalin’s Forced Famine 1932 – 1933 7,00,000 Deaths

Joseph Stalin, leader of the Soviet Union, set in motion events designed to cause a famine in the Ukraine to destroy the people there seeking independence from his rule. As a result, an estimated 7,000,000 persons perished in this farming area, known as the breadbasket of Europe, with the people deprived of the food they had grown with their own hands.

The Ukrainian independence movement actually predated the Stalin era. Ukraine, which measures about the size of France, had been under the domination of the Imperial Czars of Russia for 200 years. With the collapse of the Czarist rule in March 1917, it seemed the long-awaited opportunity for independence had finally arrived. Optimistic Ukrainians declared their country to be an independent People’s Republic and re-established the ancient capital city of Kiev as the seat of government.

However, their new-found freedom was short-lived. By the end of 1917, Vladimir Lenin, the first leader of the Soviet Union, sought to reclaim all of the areas formerly controlled by the Czars, especially the fertile Ukraine. As a result, four years of chaos and conflict followed in which Ukrainian national troops fought against Lenin’s Red Army, and also against Russia’s White Army (troops still loyal to the Czar) as well as other invading forces including the Germans and Poles.

By 1921, the battles ended with a Soviet victory while the western part of the Ukraine was divided-up among Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia. The Soviets immediately began shipping out huge amounts of grain to feed the hungry people of Moscow and other big Russian cities. Coincidentally, a drought occurred in the Ukraine, resulting in widespread starvation and a surge of popular resentment against Lenin and the Soviets.

To lessen the deepening resentment, Lenin relaxed his grip on the country, stopped taking out so much grain, and even encouraged a free-market exchange of goods. This breath of fresh air renewed the people’s interest in independence and resulted in a national revival movement celebrating their unique folk customs, language, poetry, music, arts, and Ukrainian orthodox religion.

But when Lenin died in 1924, he was succeeded by Joseph Stalin, one of the most ruthless humans ever to hold power. To Stalin, the burgeoning national revival movement and continuing loss of Soviet influence in the Ukraine was completely unacceptable. To crush the people’s free spirit, he began to employ the same methods he had successfully used within the Soviet Union. Thus, beginning in 1929, over 5,000 Ukrainian scholars, scientists, cultural and religious leaders were arrested after being falsely accused of plotting an armed revolt. Those arrested were either shot without a trial or deported to prison camps in remote areas of Russia.

Stalin also imposed the Soviet system of land management known as collectivization. This resulted in the seizure of all privately owned farmlands and livestock, in a country where 80 percent of the people were traditional village farmers. Among those farmers, were a class of people called Kulaks by the Communists. They were formerly wealthy farmers that had owned 24 or more acres, or had employed farm workers. Stalin believed any future insurrection would be led by the Kulaks, thus he proclaimed a policy aimed at “liquidating the Kulaks as a class.”

Declared “enemies of the people,” the Kulaks were left homeless and without a single possession as everything was taken from them, even their pots and pans. It was also forbidden by law for anyone to aid dispossessed Kulak families. Some researchers estimate that ten million persons were thrown out of their homes, put on railroad box cars and deported to “special settlements” in the wilderness of Siberia during this era, with up to a third of them perishing amid the frigid living conditions. Men and older boys, along with childless women and unmarried girls, also became slave-workers in Soviet-run mines and big industrial projects.

Back in the Ukraine, once-proud village farmers were by now reduced to the level of rural factory workers on large collective farms. Anyone refusing to participate in the compulsory collectivization system was simply denounced as a Kulak and deported.

A propaganda campaign was started utilizing eager young Communist activists who spread out among the country folk attempting to shore up the people’s support for the Soviet regime. However, their attempts failed. Despite the propaganda, ongoing coercion and threats, the people continued to resist through acts of rebellion and outright sabotage. They burned their own homes rather than surrender them. They took back their property, tools and farm animals from the collectives, harassed and even assassinated local Soviet authorities. This ultimately put them in direct conflict with the power and authority of Joseph Stalin.

Soviet troops and secret police were rushed in to put down the rebellion. They confronted rowdy farmers by firing warning shots above their heads. In some cases, however, they fired directly at the people. Stalin’s secret police (GPU, predecessor of the KGB) also went to work waging a campaign of terror designed to break the people’s will. GPU squads systematically attacked and killed uncooperative farmers.

But the resistance continued. The people simply refused to become cogs in the Soviet farm machine and remained stubbornly determined to return to their pre-Soviet farming lifestyle. Some refused to work at all, leaving the wheat and oats to rot in unharvested fields. Once again, they were placing themselves in conflict with Stalin.

In Moscow, Stalin responded to their unyielding defiance by dictating a policy that would deliberately cause mass starvation and result in the deaths of millions.

By mid 1932, nearly 75 percent of the farms in the Ukraine had been forcibly collectivized. On Stalin’s orders, mandatory quotas of foodstuffs to be shipped out to the Soviet Union were drastically increased in August, October and again in January 1933, until there was simply no food remaining to feed the people of the Ukraine.

Much of the hugely abundant wheat crop harvested by the Ukrainians that year was dumped on the foreign market to generate cash to aid Stalin’s Five Year Plan for the modernization of the Soviet Union and also to help finance his massive military buildup. If the wheat had remained in the Ukraine, it was estimated to have been enough to feed all of the people there for up to two years.

Ukrainian Communists urgently appealed to Moscow for a reduction in the grain quotas and also asked for emergency food aid. Stalin responded by denouncing them and rushed in over 100,000 fiercely loyal Russian soldiers to purge the Ukrainian Communist Party. The Soviets then sealed off the borders of the Ukraine, preventing any food from entering, in effect turning the country into a gigantic concentration camp. Soviet police troops inside the Ukraine also went house to house seizing any stored up food, leaving farm families without a morsel. All food was considered to be the “sacred” property of the State. Anyone caught stealing State property, even an ear of corn or stubble of wheat, could be shot or imprisoned for not less than ten years.

Starvation quickly ensued throughout the Ukraine, with the most vulnerable, children and the elderly, first feeling the effects of malnutrition. The once-smiling young faces of children vanished forever amid the constant pain of hunger. It gnawed away at their bellies, which became grossly swollen, while their arms and legs became like sticks as they slowly starved to death.

Mothers in the countryside sometimes tossed their emaciated children onto passing railroad cars traveling toward cities such as Kiev in the hope someone there would take pity. But in the cities, children and adults who had already flocked there from the countryside were dropping dead in the streets, with their bodies carted away in horse-drawn wagons to be dumped in mass graves. Occasionally, people lying on the sidewalk who were thought to be dead, but were actually still alive, were also carted away and buried.

While police and Communist Party officials remained quite well fed, desperate Ukrainians ate leaves off bushes and trees, killed dogs, cats, frogs, mice and birds then cooked them. Others, gone mad with hunger, resorted to cannibalism, with parents sometimes even eating their own children.

Meanwhile, nearby Soviet-controlled granaries were said to be bursting at the seams from huge stocks of ‘reserve’ grain, which had not yet been shipped out of the Ukraine. In some locations, grain and potatoes were piled in the open, protected by barbed wire and armed GPU guards who shot down anyone attempting to take the food. Farm animals, considered necessary for production, were allowed to be fed, while the people living among them had absolutely nothing to eat.

By the spring of 1933, the height of the famine, an estimated 25,000 persons died every day in the Ukraine. Entire villages were perishing. In Europe, America and Canada, persons of Ukrainian descent and others responded to news reports of the famine by sending in food supplies. But Soviet authorities halted all food shipments at the border. It was the official policy of the Soviet Union to deny the existence of a famine and thus to refuse any outside assistance. Anyone claiming that there was in fact a famine was accused of spreading anti-Soviet propaganda. Inside the Soviet Union, a person could be arrested for even using the word ‘famine’ or ‘hunger’ or ‘starvation’ in a sentence.

The Soviets bolstered their famine denial by duping members of the foreign press and international celebrities through carefully staged photo opportunities in the Soviet Union and the Ukraine. The writer George Bernard Shaw, along with a group of British socialites, visited the Soviet Union and came away with a favorable impression which he disseminated to the world. Former French Premier Edouard Herriot was given a five-day stage-managed tour of the Ukraine, viewing spruced-up streets in Kiev and inspecting a ‘model’ collective farm. He also came away with a favorable impression and even declared there was indeed no famine.

Back in Moscow, six British engineers working in the Soviet Union were arrested and charged with sabotage, espionage and bribery, and threatened with the death penalty. The sensational show trial that followed was actually a cynical ruse to deflect the attention of foreign journalists from the famine. Journalists were warned they would be shut out of the trial completely if they wrote news stories about the famine. Most of the foreign press corp yielded to the Soviet demand and either didn’t cover the famine or wrote stories sympathetic to the official Soviet propaganda line that it didn’t exist. Among those was Pulitzer Prize winning reporter Walter Duranty of the New York Times who sent one dispatch stating “…all talk of famine now is ridiculous.”

Outside the Soviet Union, governments of the West adopted a passive attitude toward the famine, although most of them had become aware of the true suffering in the Ukraine through confidential diplomatic channels. In November 1933, the United States, under its new president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, even chose to formally recognized Stalin’s Communist government and also negotiated a sweeping new trade agreement. The following year, the pattern of denial in the West culminated with the admission of the Soviet Union into the League of Nations.

Stalin’s Five Year Plan for the modernization of the Soviet Union depended largely on the purchase of massive amounts of manufactured goods and technology from Western nations. Those nations were unwilling to disrupt lucrative trade agreements with the Soviet Union in order to pursue the matter of the famine.

By the end of 1933, nearly 25 percent of the population of the Ukraine, including three million children, had perished. The Kulaks as a class were destroyed and an entire nation of village farmers had been laid low. With his immediate objectives now achieved, Stalin allowed food distribution to resume inside the Ukraine and the famine subsided. However, political persecutions and further round-ups of ‘enemies’ continued unchecked in the years following the famine, interrupted only in June 1941 when Nazi troops stormed into the country. Hitler’s troops, like all previous invaders, arrived in the Ukraine to rob the breadbasket of Europe and simply replaced one reign of terror with another.

Armenians in Turkey 1915 – 1918 1,500,000 Deaths

The first genocide of the 20th Century occurred when two million Armenians living in Turkey were eliminated from their historic homeland through forced deportations and massacres.

For three thousand years, a thriving Armenian community had existed inside the vast region of the Middle East bordered by the Black, Mediterranean and Caspian Seas. The area, known as Asia Minor, stands at the crossroads of three continents; Europe, Asia and Africa. Great powers rose and fell over the many centuries and the Armenian homeland was at various times ruled by Persians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs and Mongols.

Despite the repeated invasions and occupations, Armenian pride and cultural identity never wavered. The snow-capped peak of Mount Ararat became its focal point and by 600 BC Armenia as a nation sprang into being. Following the advent of Christianity, Armenia became the very first nation to accept it as the state religion. A golden era of peace and prosperity followed which saw the invention of a distinct alphabet, a flourishing of literature, art, commerce, and a unique style of architecture. By the 10th century, Armenians had established a new capital at Ani, affectionately called the ‘city of a thousand and one churches.’

In the eleventh century, the first Turkish invasion of the Armenian homeland occurred. Thus began several hundred years of rule by Muslim Turks. By the sixteenth century, Armenia had been absorbed into the vast and mighty Ottoman Empire. At its peak, this Turkish empire included much of Southeast Europe, North Africa, and almost all of the Middle East.

But by the 1800s the once powerful Ottoman Empire was in serious decline. For centuries, it had spurned technological and economic progress, while the nations of Europe had embraced innovation and became industrial giants. Turkish armies had once been virtually invincible. Now, they lost battle after battle to modern European armies.

As the empire gradually disintegrated, formerly subject peoples including the Greeks, Serbs and Romanians achieved their long-awaited independence. Only the Armenians and the Arabs of the Middle East remained stuck in the backward and nearly bankrupt empire, now under the autocratic rule of Sultan Abdul Hamid.

By the 1890s, young Armenians began to press for political reforms, calling for a constitutional government, the right to vote and an end to discriminatory practices such as special taxes levied solely against them because they were Christians. The despotic Sultan responded to their pleas with brutal persecutions. Between 1894 and 1896 over 100,000 inhabitants of Armenian villages were massacred during widespread pogroms conducted by the Sultan’s special regiments.

But the Sultan’s days were numbered. In July 1908, reform-minded Turkish nationalists known as “Young Turks” forced the Sultan to allow a constitutional government and guarantee basic rights. The Young Turks were ambitious junior officers in the Turkish Army who hoped to halt their country’s steady decline.

Armenians in Turkey were delighted with this sudden turn of events and its prospects for a brighter future. Jubilant public rallies were held attended by both Turks and Armenians with banners held high calling for freedom, equality and justice.

However, their hopes were dashed when three of the Young Turks seized full control of the government via a coup in 1913. This triumvirate of Young Turks, consisting of Mehmed Talaat, Ismail Enver and Ahmed Djemal, came to wield dictatorial powers and concocted their own ambitious plans for the future of Turkey. They wanted to unite all of the Turkic peoples in the entire region while expanding the borders of Turkey eastward across the Caucasus all the way into Central Asia. This would create a new Turkish empire, a “great and eternal land” called Turan with one language and one religion.

But there was a big problem. The traditional historic homeland of Armenia lay right in the path of their plans to expand eastward. And on that land was a large population of Christian Armenians totaling some two million persons, making up about 10 percent of Turkey’s overall population.

Along with the Young Turk’s newfound “Turanism” there was a dramatic rise in Islamic fundamentalist agitation throughout Turkey. Christian Armenians were once again branded as infidels (non-believers in Islam). Anti-Armenian demonstrations were staged by young Islamic extremists, sometimes leading to violence. During one such outbreak in 1909, two hundred villages were plundered and over 30,000 persons massacred in the Cilicia district on the Mediterranean coast. Throughout Turkey, sporadic local attacks against Armenians continued unchecked over the next several years.

There were also big cultural differences between Armenians and Turks. The Armenians had always been one of the best educated communities within the old Turkish empire. Armenians were the professionals in society, the businessmen, lawyers, doctors and skilled craftsmen. And they were more open to new scientific, political and social ideas from the West (Europe and America). Children of wealthy Armenians went to Paris, Geneva or even to America to complete their education.

By contrast, the majority of Turks were illiterate peasant farmers and small shop keepers. Leaders of the Ottoman Empire had traditionally placed little value on education and not a single institute of higher learning could be found within their old empire. The various autocratic and despotic rulers throughout the empire’s history had valued loyalty and blind obedience above all. Their uneducated subjects had never heard of democracy or liberalism and thus had no inclination toward political reform. But this was not the case with the better educated Armenians who sought political and social reforms that would improve life for themselves and Turkey’s other minorities.

The Young Turks decided to glorify the virtues of simple Turkish peasantry at the expense of the Armenians in order to capture peasant loyalty. They exploited the religious, cultural, economic and political differences between Turks and Armenians so that the average Turk came to regard Armenians as strangers among them.

When World War I broke out in 1914, leaders of the Young Turk regime sided with the Central Powers (Germany and Austria-Hungary). The outbreak of war would provide the perfect opportunity to solve the “Armenian question” once and for all. The world’s attention became fixed upon the battlegrounds of France and Belgium where the young men of Europe were soon falling dead by the hundreds of thousands. The Eastern Front eventually included the border between Turkey and Russia. With war at hand, unusual measures involving the civilian population would not seem too out of the ordinary.

As a prelude to the coming action, Turks disarmed the entire Armenian population under the pretext that the people were naturally sympathetic toward Christian Russia. Every last rifle and pistol was forcibly seized, with severe penalties for anyone who failed to turn in a weapon. Quite a few Armenian men actually purchased a weapon from local Turks or Kurds (nomadic Muslim tribesmen) at very high prices so they would have something to turn in.

At this time, about forty thousand Armenian men were serving in the Turkish Army. In the fall and winter of 1914, all of their weapons were confiscated and they were put into slave labor battalions building roads or were used as human pack animals. Under the brutal work conditions they suffered a very high death rate. Those who survived would soon be shot outright. For the time had come to move against the Armenians.

The decision to annihilate the entire population came directly from the ruling triumvirate of ultra-nationalist Young Turks. The actual extermination orders were transmitted in coded telegrams to all provincial governors throughout Turkey. Armed roundups began on the evening of April 24, 1915, as 300 Armenian political leaders, educators, writers, clergy and dignitaries in Constantinople (present day Istanbul) were taken from their homes, briefly jailed and tortured, then hanged or shot.

Next, there were mass arrests of Armenian men throughout the country by Turkish soldiers, police agents and bands of Turkish volunteers. The men were tied together with ropes in small groups then taken to the outskirts of their town and shot dead or bayoneted by death squads. Local Turks and Kurds armed with knives and sticks often joined in on the killing.

Then it was the turn of Armenian women, children, and the elderly. On very short notice, they were ordered to pack a few belongings and be ready to leave home, under the pretext that they were being relocated to a non-military zone for their own safety. They were actually being taken on death marches heading south toward the Syrian desert.

Most of the homes and villages left behind by the rousted Armenians were quickly occupied by Muslim Turks who assumed instant ownership of everything. In many cases, young Armenian children were spared from deportation by local Turks who took them from their families. The children were coerced into denouncing Christianity and becoming Muslims, and were then given new Turkish names. For Armenian boys the forced conversion meant they each had to endure painful circumcision as required by Islamic custom.

Individual caravans consisting of thousands of deported Armenians were escorted by Turkish gendarmes. These guards allowed roving government units of hardened criminals known as the “Special Organization” to attack the defenseless people, killing anyone they pleased. They also encouraged Kurdish bandits to raid the caravans and steal anything they wanted. In addition, an extraordinary amount of sexual abuse and rape of girls and young women occurred at the hands of the Special Organization and Kurdish bandits. Most of the attractive young females were kidnapped for a life of involuntary servitude.

The death marches, involving over a million Armenians, covered hundreds of miles and lasted months. Indirect routes through mountains and wilderness areas were deliberately chosen in order to prolong the ordeal and to keep the caravans away from Turkish villages.

Food supplies being carried by the people quickly ran out and they were usually denied further food or water. Anyone stopping to rest or lagging behind the caravan was mercilessly beaten until they rejoined the march. If they couldn’t continue they were shot. A common practice was to force all of the people in the caravan to remove every stitch of clothing and have them resume the march in the nude under the scorching sun until they dropped dead by the roadside from exhaustion and dehydration.

An estimated 75 percent of the Armenians on these marches perished, especially children and the elderly. Those who survived the ordeal were herded into the desert without a drop of water. Others were killed by being thrown off cliffs, burned alive, or drowned in rivers.

The Turkish countryside became littered with decomposing corpses. At one point, Mehmed Talaat responded to the problem by sending a coded message to all provincial leaders: “I have been advised that in certain areas unburied corpses are still to be seen. I ask you to issue the strictest instructions so that the corpses and their debris in your vilayet are buried.”

But his instructions were generally ignored. Those involved in the mass murder showed little interest in stopping to dig graves. The roadside corpses and emaciated deportees were a shocking sight to foreigners working in Turkey. Eyewitnesses included German government liaisons, American missionaries, and U.S. diplomats stationed in the country.

The Christian missionaries were often threatened with death themselves and were unable to help the people. Diplomats from the still neutral United States communicated their blunt assessments of the ongoing government actions. U.S. ambassador to Turkey, Henry Morgenthau, reported to Washington: “When the Turkish authorities gave the orders for these deportations, they were merely giving the death warrant to a whole race…”